…Continued from Part 1…

In part 1 we covered the noble aspirations of Marcel Proust’s writing. In part 2 we focus on the use of language to that end. You might not be surprised that a literary genius had very exacting standards for the use of language…

It’s worth giving some thought to how our use of language affects our lives, too.

The curse of the cliché

Proust was a proud defender of the French language and a sworn enemy of the cliché. Not just common phrases or petty bourgeoise expressions but also the common use of mindless adjectives.

For instance, he took issue with tired descriptions of a discreet moon or a blazing sunset. Though sometimes a moon would appear discreet, or a sunset ablaze, by the time those circumstances arose, the adjectives would be too exhausted to carry descriptive power.

For Proust, general observations deny the detail of our particular experience of the world and render our use of language meaningless.

It might not surprise you to learn that this great figure of letters would place such stock in the precise and honest use of language. Don’t disregard this as the idiosyncrasy of genius. This should not just be the remit of those seeking to change the world through story. Even regular words shape our lives. When we adopt generalities and cliché, we dilute the colours of our life.

Cliché gives us short-cut access to common wisdom. Being over-reliant on what is common, causes us flatten ourselves to fit into the constraints of a social envelope.

We arrive at mindless cliché along two paths.

The first is a skill issue. Yes, communication is hard, but I don’t think the limitations of a vocabulary are to blame. Even harder is the practice of awareness. A person attuned to their surroundings doesn’t need complicated language to describe it. Language used to match experience, not the other way round.

The second is social. To delve into the detail of your individual experience is to risk embarrassment in front of another. Notice how cliches and generalities do not appear when we are alone and in full embrace of our “weird”. Stepping away from what is sanctioned as “shared” experience is revealing and may elicit fear in the speaker. All sorts of masks and defensive mechanisms follow from that.

The irony - as Proust shows - is that the more detailed the description of your experience, the more likely it is to resonate with others. The universal is best expressed through the particular.

I return to a favourite whipping boy of mine. Speaking standards in the footballing world. The r/AFL subreddit has an entertaining post on player media training. One comment offers “7 rules” for avoiding the display of any meaning, thought or personality. Viewers of weekend broadcasting will be familiar with such blather. “Ahh” and “yeah-nah” do not make compelling viewing.

I would much rather listen to Brett Kirk’s sincere attempts to bring meaning to mundane Saturday Afternoons on Seven (“Thanks Basil”), than the deflective crap that peppers the television broadcast every Friday night. I also have a gripe with “sophisticated” words (think 3-4 syllables) that have crept into the canon to convey serious thought. When “conducive“ was used by a Port Adelaide Assistant Coach to describe a defensive game-style, in an interview with Roaming Brian (admittedly after the Blues had lost), I nearly vomited up the string ham from my family sized suburban pizza. Harsh though that may be, it is symbolic of a greater ill. Using banal but sanctioned words to convey general meaning. The homo erectus version of corporate speak.

My issue with general-speak is its invulnerability. It is, consciously or not, self-protective. Another example of this is when people speak in the second or third person: “you never want to lose…” “the boys are…”. Deferring to the collective to avoid exposure of your own position or experience. Consider the ease with which one can say “Love you” and the vulnerability of owning it fully and saying “I love you”. Exposure to loss and rejection makes the latter more trying.

Don’t let anybody in and you cannot be exposed seems to be a subconscious rule adopted by many. I think such a defensive approach to communication is deserving of cringe every bit as much as others receive it for self-expression (see: backlash to Brett Kirk).

Worse yet, for the speaker, it caps access to the fullness of human experience.

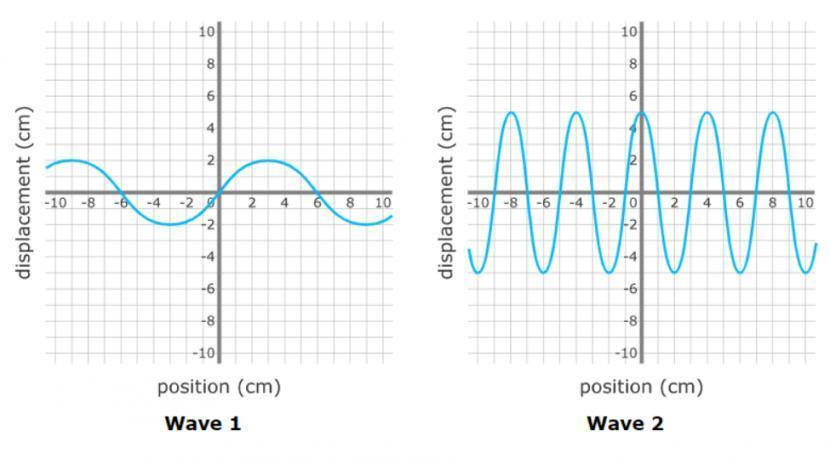

Below is a graphical representation of two waves travelling along the same distance. Notice how wave 1 is capped at an amplitude of 2? Whereas the other wave, on a higher frequency journey, displaces itself vigorously from +5 to -5 and back. General speak limits our experience of life in a similar way. It dulls our frequency. An amplitude of 2 is unrealistically vibrant for corporate speak. There concludes my use of general physics to make a point. I’m way out of my depth.

Image: Graphs displaying two distinct waves.

Be Wave 2. Embrace the full experience.

But where do we stop? Language is a finite tool. The complexity of any human experience can not be bound and precisely located in letters. Any attempt to put experience into language will be incomplete, either peppered with gaps or bulldozed by narrative.

Monsieur Proust committed his genius to the challenge of capturing life with accuracy. His seven volumes are an attempt to be exhaustively honest. Is it any wonder that he died, tired and withdrawn from the world, at 51?

Language and reality

The legal system deals daily with the difficulty of language bearing an accurate representation of reality. Painstaking care is taken to certifying something as true in a court of law. Rightly so. Our judicial system is built on the maxim that it is better to have 10 guilty men roam free, than one innocent man falsely imprisoned.1 Recreating reality through fragmentary evidence is hard. Proceed with caution when seeking to deny somebody of their liberty…Enter the law of Evidence.

When I was learning the law of evidence at university, the only enduring lesson was a non-technical one derived from a short story our professor shared with us, called ‘Funes, His Memory’ by Jorge Luis Borges.

Borges was an Argentinian writer who opened the flood-gates to a generation of Latin American modernists.2 He is a favourite of elbow-patch wearing academics.3 This short story in Fictions is about a boy called Ireneo Funes who succumbs to illness as a result of exhaustion brought on by an infinite intelligence and memory. A victim of genius, not unlike Proust.

An example of his curse:

‘With one quick look, you and I perceive three wineglasses on a table; Funes perceived every grape that had been pressed into the wine and the stalks and tendrils of its vineyard. He knew the forms of the clouds in the southern sky on the morning of April 30, 1882, and he could compare them in his memory with the veins in the marbled binding of a book he had seen only once, or with the feathers of spray lifted by an oar on the Rio Negro on the eve of the Battle of Quebracho.’

No human mind can sustain such depth of perception! Despite his mental capacities, the narrator suspects that Funes was not very good at thinking. After all, ‘to think is to ignore (or forget) differences, to generalize, to abstract.’ To think therefore, is to accept the shortest version that enables getting on with living.

Where does that leave us? Proust (and I) argue for the use of the particular and Funes warns us of the folly of going too far. Once more, the path is to be found at the mean of two extremes. Be neither Ireneo or Tyson Goldsack.4

Our task is to attune to our lives so as to really live it and use the level of language available to us to capture that experience with honesty. Incompleteness is, after all, a precondition of thinking. And living.

We owe a great deal of gratitude to dear Proust. He exhausted himself with the aspiration to uncover and express the infinite depth of life. We are left with a deep well from which we can drink, quench our thirst for knowledge of life’s mysteries and carry on living day-to-day. Enriched by the dedication to truth to which he sacrificed his life.

There concludes our series on Proustian Reflections.

What I am enjoying this week

The emergence of wonderful weather in Adelaide (not at time of publishing). The gentle descent of Springtime brining with it shorter sleeves and uplifted moods. Granted the truncated winter and absence of rain is cause for some concern….

The Rest is History Podcast. My sister ENV directed me this way. It is no longer a unique recommendation, having acquired itself every top honour belonging to the Arts in the UK. Deservedly. Dominic Sandbrook and Tom Holland are masters of telling stories and bringing historical figures to life. The amateur historian in me delights and winces as they one-two-skip-a-few over years and long periods of history. They are, after all, entertainers. (Talk about the difficulty of accurately portraying the reality of the past in words! In fact, this very difficulty (historiography) turned me off of the formal study of history in 2016. How I’ve crawled back). My most recent foray is into the life of Marie Antoinette - Queen of France (formerly Maria Antonia of Austria) in their 8 part series on the French Revolution. Do yourself a favour.

This quote on the power of reading by Writer and activist James Baldwin:

"You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who ever had been alive. Only if we face these open wounds in ourselves can we understand them in other people. An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are."

An excerpt from a famous letter from Einstein to his daughter - I found in the Friday Mojo newsletter from Ben Crowe. There is an extremely powerful force that, so far, science has not found a formal explanation to. It is a force that includes and governs all others, and is even behind any phenomenon operating in the universe and has not yet been identified by us. This universal force is LOVE…

“Play on” Jemima Montag - Australian dual bronze medalist in race-walking - in an inspiring post race interview. ‘it's a careful balance of wanting that medal but not needing it.. for your own self-worth’ Perhaps Jemima read Proustian Reflections Pt 1?

Au revoir.

A variation of Sir William Blackstone’s ratio passed on to me through another Chief Justice, my former boss.

“He, more than anyone, renovated the language of fiction and thus opened the way to a remarkable generation of Spanish-American novelists” - writes Adelaide writer in residence (and Nobel Laureate) J.M. Coetzee.

This is a tip of the hat to, if not a direct quote of, Professor NN Taleb. A member of the Pantheon here @ WW.

The aforementioned Assistant Coach who doesn’t deserve this whacking but, given the obscurity of Wandering Words, will sleep just fine.